Why I Teach: I Love Knowledge

I'm going to pile on the "why I teach" meme, comfortable that no one will tag me seeing as how I've just started here.

This started with Dr. Crazy's excellent reaction to the MLA "Why Teach Literature" panel. It's been buoyed by reaction to Stanley Fish's two columns on the delicious uselessness of literary study. And there's also the desire, spurred by Free Exchange, for professors to explain our real motivations for teaching in the face of the Horowitzian accusations of indoctrination. (And note the spring offensive of the Academic Bill of Rights supporters, just in case you thought they had finally gone away.)

I won't repeat what others have have already said more eloquently than can I. But I'll add two things.

I think the reason most academics are willing to do what we do for a fraction of what we'd earn for similarly demanding work is that we really do find discovery and sharing knowledge rewarding. I don't think that is so odd -- witness the number of people who still say that when they retire they would like to get a part-time teaching gig.

Most humanists I've spoken with share this point of view, which is why the idea of "indoctrination" is so far from the mark. Now, to be clear, we all have areas of expertise. Some of them are clearly useful. When questions of policy arise involving those areas of expertise, decision-makers should genuinely listen to what we have to say. (Not blindly follow, but genuinely listen. The ability to know the difference, and know how to listen, comes in part from a good liberal arts education.)

That said, I don't take it as my job to dictate what students should do with the knowledge, and more important ability to learn, that my teaching provides.

This started with Dr. Crazy's excellent reaction to the MLA "Why Teach Literature" panel. It's been buoyed by reaction to Stanley Fish's two columns on the delicious uselessness of literary study. And there's also the desire, spurred by Free Exchange, for professors to explain our real motivations for teaching in the face of the Horowitzian accusations of indoctrination. (And note the spring offensive of the Academic Bill of Rights supporters, just in case you thought they had finally gone away.)

I won't repeat what others have have already said more eloquently than can I. But I'll add two things.

I.

First, the Chaucer's clerk reason: I teach because I love knowledge. I've never gotten over the pure wonderfulness of learning new things and sharing what I know with others. The problem with Fish's view is that he highlights only one kind of knowledge: the recognition of aesthetic craft. That's fine, but there's more to know, and drawing strict disciplinary boundaries around knowledge doesn't work. It doesn't work for reading literature, and is especially deforming when engaging with ideas generally, something that humanists just do, whatever our primary expertise. Yes, the pure desire to know exists beyond questions of utility, but that does not preclude the idea that knowing "in a general way" leads to a host of pragmatic ends (many of which the blogs I've linked to explain in some detail.) And I would say that this thirst for knowledge is also why research and teaching, for me and many others, really do go hand-in-hand.I think the reason most academics are willing to do what we do for a fraction of what we'd earn for similarly demanding work is that we really do find discovery and sharing knowledge rewarding. I don't think that is so odd -- witness the number of people who still say that when they retire they would like to get a part-time teaching gig.

II.

The second important thing about teaching is that I recognize I have a limited role, albeit an important one. I won't change the world: my students will.Most humanists I've spoken with share this point of view, which is why the idea of "indoctrination" is so far from the mark. Now, to be clear, we all have areas of expertise. Some of them are clearly useful. When questions of policy arise involving those areas of expertise, decision-makers should genuinely listen to what we have to say. (Not blindly follow, but genuinely listen. The ability to know the difference, and know how to listen, comes in part from a good liberal arts education.)

That said, I don't take it as my job to dictate what students should do with the knowledge, and more important ability to learn, that my teaching provides.

2 Comments:

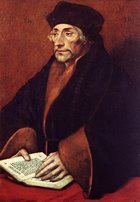

Great blog, Erasmus!

Thanks for this post and sorry we didn't pick it up earlier somehow it didn't show up in our Google or Technorati feeds (okay, the likelihood that this is true is so slim, it probably means we missed it!). You are officially now on the list of posts on the meme. Thanks again!

cps @ Free Exchange

Post a Comment

<< Home